For this edition of 5 Q’s we talk with Reno based artist Chelsea Houston, a featured HP Billboard Gallery artist for January. We discuss Houston’s artmaking process, how she navigates using different materials, the American Southwest, public art and art accessibility. Born in Maui, and Houston has resided in many western states, but now calls Nevada her home. Primarily a painter, she often weaves elements of illustration and printmaking into her pieces. Human and fauna forms strike her most, both living and post-mortem: portraiture, skeletal studies, and captures of anatomy.

1. How do you approach art making? What is your process like? The landscapes and still lifes seen in your work seem to have a photographic reference, what is your relationship with photography?

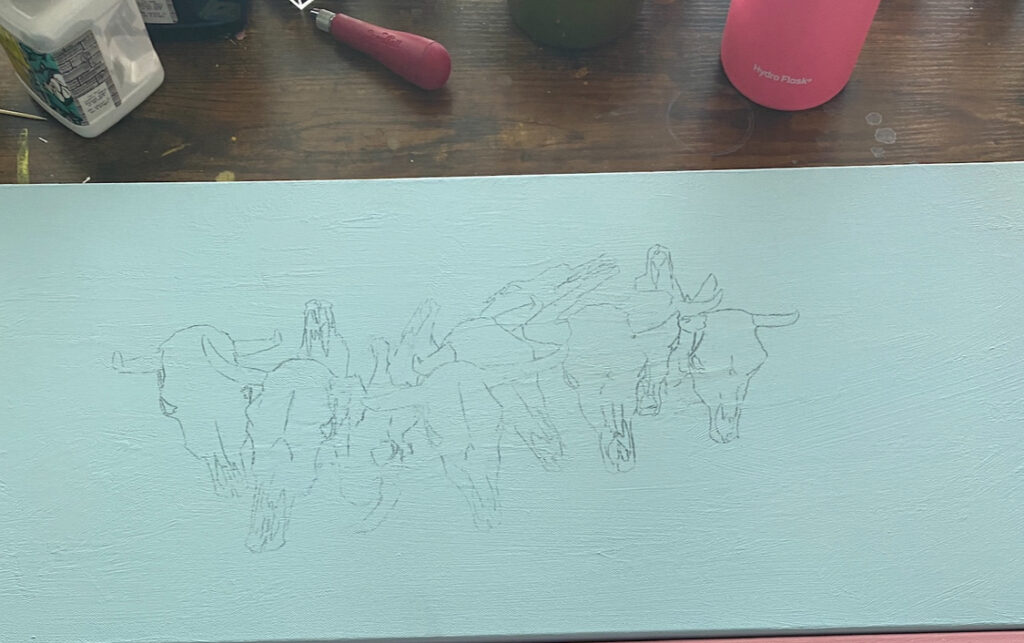

I like to keep general supplies like paint, canvas, printmaking ink and new lino blocks on-hand because I know inspiration tends to strike randomly. Having materials at the ready makes creation/exploration more immediate or at least less daunting because it’s one less step to worry about. Sometimes I’ll need a new brush, different nails, or adhesive, but my present/future self always appreciates my past-self’s foresight. From there, I mull concepts mentally, I don’t really sketch. Music is inevitable to the process too because certain songs will trigger a memory or feeling that could weave itself into whatever I’m working on.

Depending on the concept, I like looking through personal photographs, I’ll internet search here and there, but I also like taking new photos (random errands will sometimes be a goldmine). Having personal reference points – colors, textures, forms themselves makes my work feel more personal. Photographs are really important for me because sitting with a subject or painting en plein air isn’t always feasible or practical. Having a consistent visual reference point to either charcoal trace or tape up as a guide helps me ground the form/proportions of what I’m working on and enjoy more experimentation with form itself, as well as color and texture. I really use photography as a means of documentation. Photos are a foundation for freedom and inspiration.

2. Working in mixed media, from paint, to cowhide, to crystals, to doors, how important are the materials you use to give concepts to your artworks?

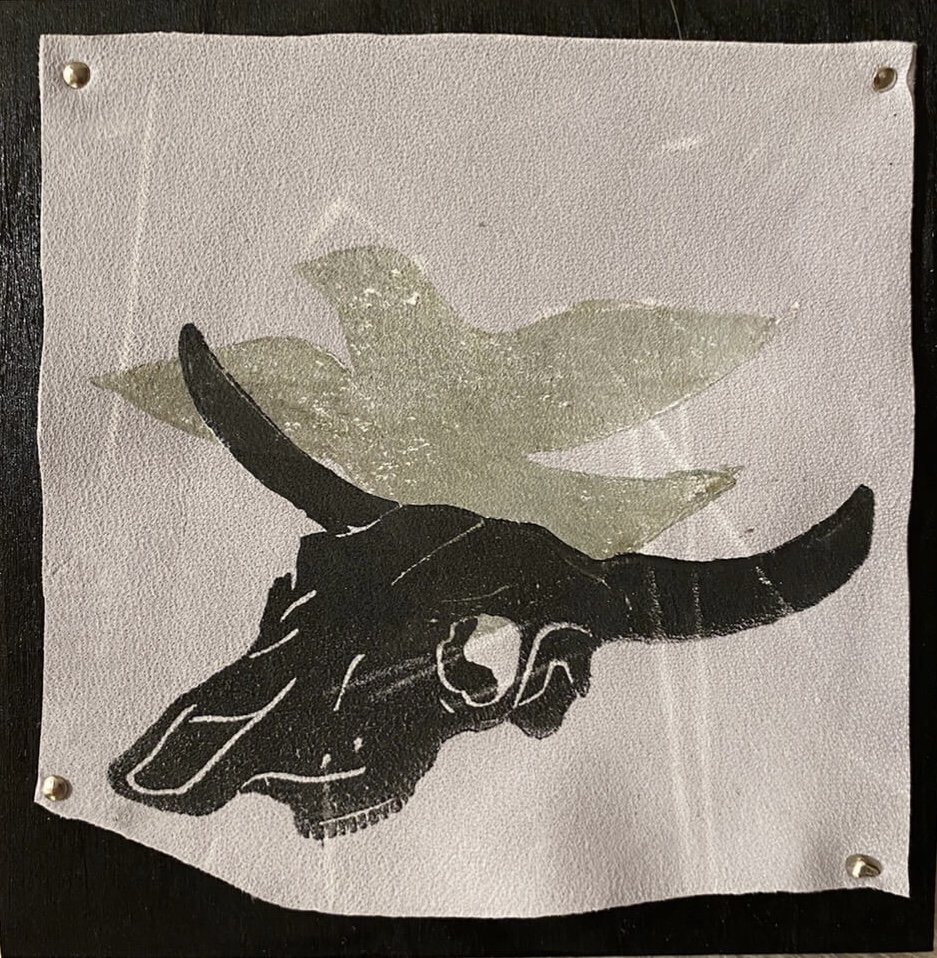

Experimentation can be a starting point for me. I really like the unpredictability of certain materials (leather, suede, crystals) and the comfort of others (acrylic paint). Crystals are polarizing for various reasons– I like this. They’re usually considered tacky (or ‘too girly’, which I like challenging) or misplaced. Leather is both exciting and daunting to work with because it’s expensive and beautiful, also the result of a once-living thing (there’s weight to that for me; I’m much more mindful and even reverent whenever I’m working with leather). The materials can control my tempo and concept – sometimes they’re the deciding factor. Exploration and the potential for unknowns (even disaster) are two tides that really shift the way I make and are really why I love creating art. I love learning through making.

3. How do the cultural and geographical aspects of the American Southwest and, more specifically, Nevada inform your art practice? What else inspires your artworks?

I moved throughout several western states a lot between the ages of 3-12, so my fascination with landscapes, skies, roadstops, and the overall weirdness of the west has stayed with me (most moves were done by car). I love the mystery and strange electricity coursing through Nevada landscapes. There’s neon, expanse, dirt, violence, kitsch, tradition, and so much unearthed. I think of stories and secrets within.

The concept of defamiliarization (or ostrananie) is one I hold close whenever I create as well. I enjoy taking something familiar or even iconic (a cow skull, for example) and turning it on it’s head a bit to make it new, fresh, or otherwise provocative. I like challenging the ordinary or otherwise overdone by adding new context – juxtaposing softer or more stereotypically feminine metallic or pastel palettes (especially pinks!) with harder or stereotypically more masculine-oriented subjects (western iconography– cow skulls, western landscapes) is one way I’ll tango with this.

I really enjoy researching various subjects and references when I’m making Nevada-centric work, as well. I take my time with the process – it’s important for me to render work properly and to honor the subject itself. For example, for the signal box I painted, I wanted to pay homage to several local Tribes and our state fish (the Lahontan cutthroat trout), a valuable food source for centuries. I featured several basketry patterns encircling the trout – each represents a specific Tribe in Northern Nevada and designs commonly found adorning baskets they would make. It took me a couple of weeks to amass accurate references to inform and bolster my proposal, however I felt proud and confident in the work because it involved tender attention and conveyed authenticity.

4. In your solo exhibition, Hi Desert, at the Sierra Arts Depot Gallery in Sparks, you listed your works for prices that reflected the area’s minimum wage. What was the thought process behind this concept? How important is it to you that art be accessible?

The Hi Desert exhibit (October 2022) was held at an especially precarious time due to multiple factors (Covid fear and fatigue, global economic collapse, heightened anxiety, etc.).

Art is a luxury for most– it isn’t food (usually), fuel, housing, heat, healthcare, etc. I understand and respect the secondary or beyond tertiary nature of purchasing art nowadays and ultimately price to sell because I want people who want my art to have it. It’s an honor to know my art is loved and desired to the point of coveting. I’m so grateful to anyone that shows up to see my work (on purpose or not).

Dignity and pride comes from accessibility– to be able to afford a one of a kind, handmade piece of art is precious (it also feels fucking great!). The rush I get from being able to purchase something I really love from an artist is a feeling I try to impart whenever I’m selling work. I’ll ensure I have multiple price points and options (for example, prints of paintings vs. originals have been successful and let the work live on a few times over at a gentler price point and usually smaller size, which can be more practical for some).

I think of the choices that factor into an on-site (exhibit) purchase – the time and effort to get there, the hours worked to earn the money to pay for the piece, the cost of fuel to get to the show, etc. I truly appreciate the choices made to choose a piece of my work and the way I consider pricing is a reflection of that.

5. You are an elected member on the Public Art Committee for the City of Reno, and have created your own public artworks, what do you value in public art? How do you see public art benefiting the environment it is in?

My first solo public art piece was painting a signal box and that gave me the confidence to even consider applying for a seat on City of Reno’s Public Art Committee. That experience and gained perspective really catalyzed my interest in participating in the process around public art. As a working artist, I saw from my lens primarily, however I wanted to learn and understand art’s community relationship, it’s environmental impact, and future-driven implications (how it can shape and honor an area vs. an interior space). When I was painting my signal box, countless passersby stopped to comment on my work, share their own art experiences and sometimes needs, and even lingered a bit to watch me paint, sketch a new part of the work, measure, etc. The public participation in public art is a crucial part of the process for me. Public art involves (includes) people and is the result of questions and conversation. I value the inevitable participation that ensues from public art—excitement, story sharing, kindness— the humanity of it, which is what art is.

Public art, in it’s simplest form, can act as a landmark or form of mapping—a charming and whimsical method of marking locations, meeting up with someone, or remembering a location based on its neighboring features. Public art adds character to it’s environment, no matter what it is. The dynamic tension (sometimes inspiring, sometimes confusing or even inciting) is the thing that sets this breed of art aside from art inside a controlled environment.

STANLEY HUMPHRIES

Mar 15, 2024 -

BEAUTIFUL WORK! I AM YOUR BIOLOGICAL DAD, STANLEY HUMPHRIES. I LOVE YOU AND THINK OF YOU DAILY, ESPECIALLY ON MARCH 12TH, YOUR BIRTHDAY. LOVE, STAN